I am a retired English professor. I have a Ph.D. in liteary studies, but for the greatest part of my career I directed writing programs, initially as a concentration within the English major at Moravian College (since 2022, Moravian University) then a writing-across-the curriculum program that I helped launch in 2001. In the course of that work, I pretty much abandoned the profession of literature to learn Rhetoric and Composition. Eventually, I expanded my undrstanding of writing to include multi-modal composition. The germ of this website lay in a digital portfolio assignment I gave to a class at Penn State University’s Abington campus, where I was hired to teach multi-modal writing. I made the site as a rough model for what I was asking students to do as a semester project.

I’m writing in the public sphere rather than keeping a journal because I believe rhetoric is important and omnipresent, as the quote from Stephen Mailloux suggests. In 2012, I attended an “immersive” experience under the direction of Richard Miller at Rutgers U. It was called “Creative Critical Writing,” and his point was that publishing online was a way to get to readers without having to go through the gatekeeping that editors do. For me, it was a chance to have greater control over what I write. In 1992, I signed a contract with HarperCollins publishers to produce a college-level introductory literarture text book. I worked on that project for four years, with the book, Reading and Responding to Poetry, Fiction, Drama, and the Essay, published in 1996. I learned then that once a book is published, it’s is no longer the writer’s own. Writing the book was exciting, demanding, and exhausting, but it was mine. Once it was published, it was just another commercial project; as it happens, it was a commercial failure, no matter how good it actually was. My editors at HarperCollins were great: receptive to and supportive of my ideas and my approach to reading literature in the college classroom. But for a textbook to succeed commercially, it has to be adopted by colleges. That means more gatekeepers in the form of curriculum committees, academic departments, even individual professors. As I was writing the book, my audience was students; I didn’t fully appreciate that in order for students to read it, a lot of non-students had to approve. So what Richard Miller preached in that short summer program at Rutgers resonated with me.

A Fordham Cap

Alas, I no longer have the Fordham U. ballcap I bought about 25 years ago. I do have a story about it though.

Teaching at Moravian College, I would sometimes use spring break to get a day in the city. Sometimes I’d have an agenda, but mostly I just wanted to feel the vibe on the streets. From Bethlehem, PA, it’s an easy bus ride to the PABT. Philadelphia is closer, but harder to get to (unfortunately).

It’s a nice enough March day in the late 1990s, but in Manhattan it seems always to be chillier than I expect it will be. Departing my bus, I’m walking up 8th Avenue. No special destination in mind, but before I can even think of one I start to feel underdressed. Not in terms of fashion, in terms of comfort. My outfit of slacks, dress shirt, and sport coat will, I believe, make me blend in, not look like the out-of-towner I am. But it’s not warm enough.

As I pass the shops along the street, I think a t-shirt might do the trick. But I don’t want a total one-off, like an “I Love NY” shirt or one that says “Do I Look Like a Fucking People Person?” which are plentiful and cheap. I remember that Fordham University has a campus at Lincoln Center. Maybe they have a bookstore. Maybe I can buy a t-shirt there, one that would be comfortable but also wearable at home.

To Lincoln Center I walk, and yes, there is a bookstore. Indeed they have t-shirts. The best buy, though, is a combination shirt and cap: a grey t-shirt with “Fordham” stenciled across the chest in cardinal and a ballcap with “Fordham” stitched on it in white, more or less like the one pictured above. Perfect!

I go into the rest room, take off my coat and dress shirt, slip on the t-shirt, put my shirt and jacket back on and don the ballcap. Ready to hit the streets for sure!

I visit a museum or two (I don’t remember which, and it doesn’t really matter for the rhetorical point of this story) and catch the subway downtown. Find a bar/restaurant in the Village to grab a bite and a pint. All good. But once I finish my meal, it seems too early to catch the bus back to Bethelehem. I wonder what I can do for a couple of hours. It occurs to me that Pitt is playing UConn in the Big East men’s basketball tournament at Madison Square Garden. Pitt had a pretty good team at the time, and UConn was always good. I catch another train uptown and make for MSG.

There is a biggish crowd outside, but I make my way through it and find the ticket windows. I have no idea what a ticket to the game will cost, but I’m ready to buy one on the more economical end of the scale. As I get within two or three people from the window, a face appears and announces “No more tickets.” The game is sold out.

Like other would-be spectators, I stand there wondering what to do. At which point I hear a loud voice crying, “Tickets! Two tickets for UConn- Pitt!” I turn and see a big 50-something white man wearing a Boston Red Sox cap, striding through the lobby waving tickets in his hand and saying again, “Tickets for UConn-Pitt! Who wants to buy?” I stop him and say “I’ll buy one from you.”

“How much will you give me?” he replies. I have no idea. I don’t ask where the seats are. I say, “Uh, twenty-five dollars?” Whereupon he looks at me incredulously, throws back his head and bellows, “Twenty-five bucks! Twenty-five bucks!” Then he looks around at the people who are there and hollers, “Can you believe this? Twenty-five bucks!” Then the clincher. He laughs loud and says, “Twenty-five bucks! What do you expect from a guy wearing a Fordham cap?”

You just never know: Rhetoric in sending a sympathy card

There was this student — I’ll call her Sadie — in one of my classes at Moravian College in the mid-90s. She was one of those people whose body language in the first week of the semester said clearly, “I don’t want to be here.” I noticed but did not call her out. After a while, though, she seemed to respond to my student-centered approach and began to perk up and engage. She was smart, sensitive, and articulate, although troubled. Divorced parents, but that wasn’t her only problem. She just came from a different place, socially and emotionally, than most of her classmates.

She did well in that class — finished with a B, at least. At the time, I was close friends with a political science professor who also knew Sadie as a student. This guy, I’ll call him Gray, appreciated having troubled students so he could burrow into their problems and provide a caring listener. We shared some basic information about her, nothing too personal, but we were aware that she needed special handling.

At the end of that semester, we learned that Sadie was dead. That was the official word from the college. Gray, with his extra-sensitive radar for troubled students, learned the circumstances: she had overdosed on heroin.

Sadie, who was a commuter at a residential college, had few friends among her Moravian classmates; she went her own way. Along that way, she met a guy who was a user of hard drugs. Then fate intruded.

One May Saturday, she was walking over to Lehigh University, our across-the-river neighbor in Bethlehem. To get to “The Hill,” as the social scene at Lehigh was called, a pedestrian had to cross the Hill-to-Hill Bridge over the Lehigh River. Not usually a problem, but on this day there’d been a traffic accident on the bridge that included a chemical spill. The bridge was closed to all traffic, vehicular and pedestrian. Sadie, though, being independent-minded, knew that she could easily climb the railroad trestle that roughly paralleled the H-to-H Bridge and cross the river that way. There she met her druggie friend, who invited her to shoot up with him. She accepted. He survived; she did not.

The sudden death of any student is shocking and deeply disturbing, especially at a small college where teachers may get to know and work closely with students, as I and Gray had with Sadie. Her funeral was set during finals week. Talking with Gray, I said I’d send a card to Sadie’s mother. Which I did. It was a secular card. I’m not conventionally religious, and Gray was an atheist, but I found something generically appropriate. I never know what to say to someone grieving, especially a mother grieving her child who had, essentially, been murdered. At the time, my head was full of an album by Iris Dement: her debut, I think it was, called Infamous Angel. Words from the title song came to me, and I put them in my card: “Infamous Angel, going home.” Signed my name and Gray’s and dropped it in the mail.

A few days later, Sadie’s mother phoned me. Touched by the card and the expression that two of her daughter’s profs had sent, she pressed me for the source of the lines I had quoted. I told her; she thanked me. Then I called Gray to tell him of this interaction. He knew not the song or the words. When I told him, his knees dropped to the floor (in a manner of speaking) and his temper rose. He scolded me for attaching his name to a religious sentiment. He got no apology from me, and for a while we weren’t on speaking terms.

Infamous Angel includes several gospel songs, originals by Ms. Dement. No, I’m not religious, but neither am I an atheist. I can appreciate originality and certain creative expressions of belief. Here, without apology, is Iris’s song:

Getting to Normal

I am writing this essay more than a decade after I made a camping/biking trip to the Midwest. On that trip, as with similar excursions in 2009 and 2011, I brought my (now ancient) Flip camera with me and captured some video. (The camera was hand-held, hence the shakiness of many of the shots linked in this essay.) In 2014, I was still thinking about movie-making. It had been only six years since my learning experience at the DMAC (Digital Media and Composition) Institute I had attended at Ohio State U.; only three years since my second of two trips to the Pine Creek Trail in north-central Pa.; and just two years since I completed the “Cycling the Pine Creek Trail” interactive essay that resides elsewhere on this site. The year 2014 marked the end of certain aspects of my life – or at least of my professional life. It was my final visit to the Conference of Writing Program Administrators, which at the time I thought would be my final visit to any Writing-Studies-related conference. It was also the end of my full-time teaching career, as I took my retirement that year. So I beg my reader’s indulgence with my dusty memory banks. I did annotate my videos a couple of years ago, but little details have slipped away. For a long while, though, I have felt that I owed it to the time I spent and the video capturing I did to write this piece and post it. I will borrow from that older essay the “act-suffer-learn” rhetorical paradigm; it was useful before, and I had it in mind while traveling from my home in eastern Pennsylvania as far west as central Illinois in July of 2014. Still, this essay is not as academic or intellectual as the previous, which featured that element at the suggestion of Prof. Richard Miller, whose “immersive” fortnight in “Creative Critical Writing” I attended at Rutgers U. in May 2012 (and out of which came the “Cycling the Pine Creek Trail” piece.)

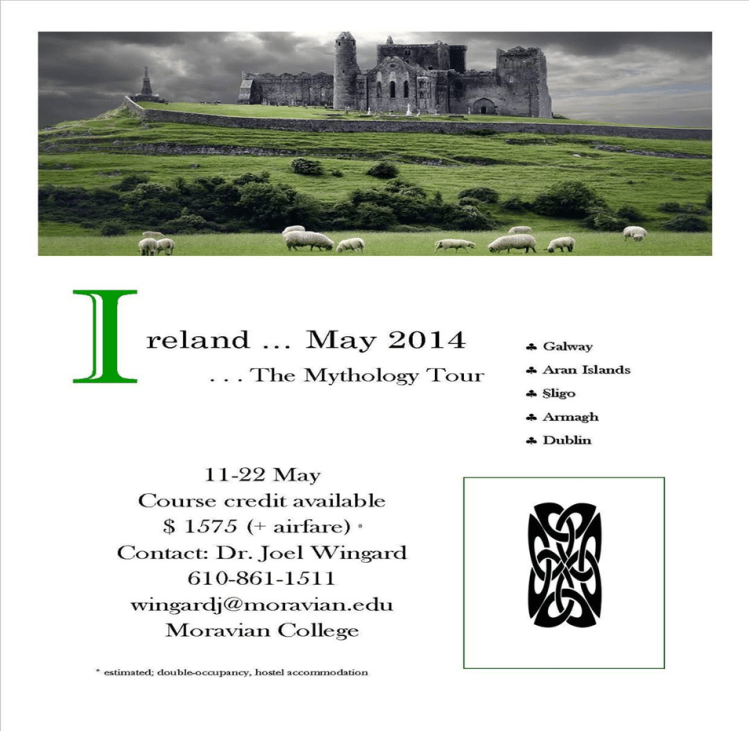

The motivation for a biking/camping trip in eleven years ago was that I did not make a trip to Ireland with Moravian College students in May 2014. Even though my employer would have underwritten many of my expenses for such a trip, it still wasn’t going to be cheap. For various reasons, the trip did not attract enough people (students or otherwise) to make it viable, so, sad to say, I cancelled it. I had not been to Ireland in more than a decade (after making 9-10 trips between 1985 and 2001), and I had not taken students since 1999. A tour of places associated with ancient myths was promising to be the best yet, but I had to put my disappointment behind me and not look too deeply into the failure of this project. Here is my publicity poster for the proposed Ireland trip:

As I was facing retirement from more than 30 years as a college English professor, I thought my days of attending professional conferences were over as of the annual college composition conference in Indianapolis in March. At a meeting at that very conference, however, it was announced that for the annual summer conference of a more specialized professional group (the CWPA), dormitory accommodation at Illinois State U. in Normal, Illinois, would be available at $30 per night. That made the prospect of attending this more within reach.

Figure 1 Giving my rare WPA ballcap to Prof. Michael Day (Northern Ill. U.) at my final CWPA summer meeting.

I was also told on the down-low that even at a relatively late date, I might still get a proposal accepted for a presentation at the CWPA conference. If I were to present, I could get some financial support from my college to attend. I figured that I could get something of an “adventure vacation” out of a trip to Illinois for the conference if I drove there, took my bike, and camped out a couple of nights enroute. (I am, by the way, an old-school tent camper; no rv’s for me!) This would also be relatively inexpensive because no airfare was involved and because campsites typically cost less per night than hotel or motel rooms. The conference fee was high, but it paid for most of the meals during its 3-4 day run, and I had no problem with staying in a spartan college dorm room for three nights. In other years when this conference was sited on or close to a university campus, dorm accommodation had been available, and I took that option for brief stays at the U. of North Carolina-Charlotte, the U. of Delaware, and the U. of Alaska-Anchorage. It was all good enough; I’m not someone who needs a lot of luxury anyway. I did have something related to the conference theme that I could present on, so I wrote that up and submitted it. It was accepted, and I started making plans.

I scouted out rails-to-trails that I might ride on this trip. A trail had to be long enough that I couldn’t ride it round-trip in one day (i.e., 40 miles or longer), it had to be close enough to a state park where I could camp, and, if I wanted to ride the Thursday of the conference (which would kick off with a keynote that evening), an Illinois trail had to be reasonably close to Normal. (hahaha!) I found some likely possibilities in Indiana and Illinois: the Cardinal Greenway Trail in eastern Indiana and and the Rock Island Trail in central Illinois. I was working backwards in that I first identified the RIT because it looked like I could get to Normal with a short drive from the second day’s ride.

I made campground reservations online for two nights each at Indiana and Illinois state parks. Even eastern Indiana was more than a day’s drive from where I live in eastern Pennsylvania, so I arranged to spend a night at the home of my brother Jan in the suburbs south of Pittsburgh. Then I would make it to White River Memorial State Park near Richmond, Indiana, the next day. I’d ride the Cardinal Greenway Trail for two days, then drive further west into Illinois and ride the Rock Island Trail over two days. So: four nights of camping, four days of biking, and four days of conferencing.

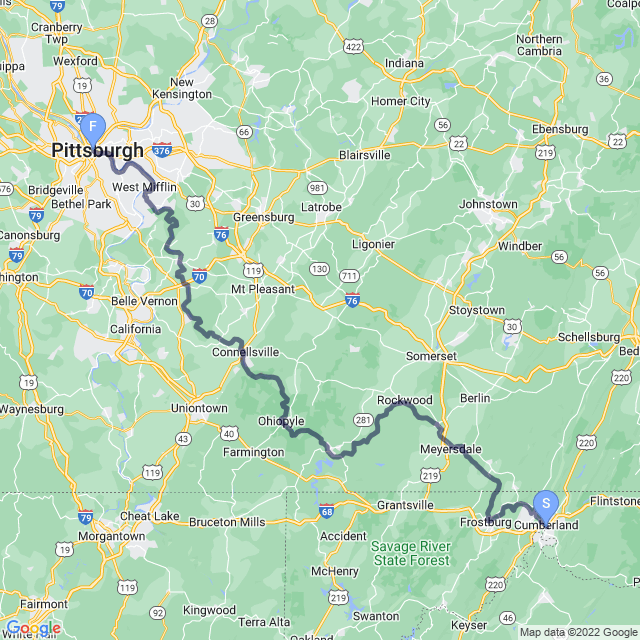

But as I thought in more detail about this trip, I realized I might be able to squeeze in rides on two other trails that I would pass enroute to Illinois. One was a portion of the Great Allegheny Passage Trail, which runs more than 150 miles between Washington, D.C., and Pittsburgh; the other was the Olentangy River Trail in Columbus, Ohio. I’d long wanted to explore the GAPT, if not its entirety then at least part of it, and a glance at a map showed me that I could get to a trailhead off the Pennsylvania Turnpike at Somerset, about 60 miles east of my brother’s house in Bethel Park.

So I left home on a Saturday with some time built in to ride at least a little bit of the Laurel Highlands portion of the GAPT before driving on to my brother’s house. Just to be able to say I’d sampled the trail.

So that was one “extra”; as to the Olentangy River Trail, I saw that if I got a decently early start away from my brother Jan’s house on Sunday morning, I could stop off briefly in Columbus, Ohio, ride at least some of that trail, and still get to the park in Indiana before the sun went down. Why did I want to complicate things like this? Well, because I had spent a couple of weeks at the DMAC at Ohio State U. in the summer of 2008, at which time I had brought my bike with me and rode the Olentangy River Trail at least some almost every day I was there.

Thinking I could commute to the OSU campus by bicycle, I had even booked a motel that looked not too far from a trailhead. That plan didn’t last too long. For one thing, it meant riding the couple of miles between the motel and the trailhead through busy city streets; for another, I was still a fairly novice and nervous cyclist in May 2008. Six years and thousands of trail miles later, though, I was feeling nostalgic for my stay in Columbus and remembering some of the scenes of the ORT fondly. (For one thing, the trail went through residential neighborhood streets at one point, a nice middle-class neighborhood in north Columbus. This was unusual in my experience.)

The detour to the GAPT in the Laurel Highlands of Pennsylvania was fun and rewarding. It also demonstrated the act-suffer-learn paradigm of the rhetoric of travel. In my haste to sample some of this trail, I left my camera in my car, which is too bad considering the little adventure I had. Sans video, you will just have to take my word for the veracity of what happened. The trail twice crosses the Casselman River within a short distance, although I didn’t know that when I started riding. I came to the first crossing, which afforded a nice view of the river below and people sunning on a rock ledge and swimming in a deep pool in front of it. At the far end of the bridge there was a tunnel from the old railroad that ran there, but it was barricaded. A sign showed a detour around the hill through which the tunnel went. I rode a couple of miles on the detour, wanting to see the other end of the tunnel. But as I rode, I saw what looked to be a landfill looming to my right on the hill above the tunnel. Disgusting, even though I wasn’t surprised because the mountains of Pennsylvania are pocked with landfills, Pennsylvania being one of the country’s leading trash-importing states. So a bit disillusioned, I turned around and rode back to the bridge. At this point, I took a break and lit a joint. I was being discreet about smoking it: cupping it in my hand which I held close to my body and leaning against the bridge railing. There was no one around except the river swimmers, so I wasn’t worried about someone noticing what I was doing. While I was doing this, though, along the trail came a trio of 20-somethings, two men and a woman. Their bikes were laden with full paniers, and indeed, as they told me later, they were making a multi-day trip on the trail and camping along the way. They passed me heading east but shortly thereafter one of the men turned around and approached me. Our conversation went like this:

Me: Hey. What’s up?

Him: Do you want to smoke?

Me: I am smoking.

Him: I know; that’s why I asked if you wanted to smoke.

Me: But I am smoking!

Him: I mean do you want to smoke weed?

Me: I am smoking weed!

Him: I mean do you want to smoke weed with us?

By this time, his two friends had caught up with him, and I shared my J with them. The other guy produced a bag of pot and a homemade bong. It was a 2-liter soda bottle with about the bottom third cut off. They had a pipe bowl that threaded down over the top of the bottle, which the guy loaded up with weed. The other guy held the bottle with one hand and with the other he shoved what looked like a bread wrapper up inside it close to the top. When the first guy lit off the pipe-load, the second guy slowly drew his hand down through the bottle allowing the bottle to fill with smoke but not leak out. Then the first guy unscrewed the pipe bowl from the top of the bottle and offered it to me to take a hit. It was a lot of smoke, but cool and not harsh at all. And what a hit! No way I could inhale it all, but we passed the bottle around and emptied out its contents. Then the guy set it up again and we all had another round. Turns out these three (or so they told me) had a policy of smoking each day of their trip with someone they found along the trail. Why did they pick me? Maybe because I was wearing this rad piratic cycling jersey.

Whatever, one of them also told me that I had given up too soon on my ride, that if I went back westward another mile or so, I would come around to the other side of the tunnel and an even better view of the river. And no, what I had seen was not a landfill; it was a new cut for a rail line. Indeed, when we all split up and I followed the guy’s advice, I saw how I’d been wrong before, and the view at the second bridge was worth the effort to get to. I had acted by riding that afternoon in the first place and by attracting the notice of the trio of stoners. I suffered (experienced) the interlude with them. And I learned about the second bridge and the non-landfill. This was a great start to my trip despite the fact that I have no video evidence of the day. {I do have an aside, however; after I’d returned home I visited a friend who was also my source for weed. I told him about my encounter with the stoners on the trail, and we had a laugh about it. I told him also that I was planning to write about it, but I was worried about my wife reading my narrative and learning that I had broken a promise not to carry drugs with me. Somehow, I said, I would have to get inventive about this encounter. My friend – Porter is his name – is also a writer, a professional writer. And he stands about 5’4”. He got right up in my face and fairly spat out the words: “Write the truth or write fiction!” I learned something right there!}

I made it to Jan’s house in time for dinner that Saturday night too, so my little indulgence didn’t inconvenience him. The next day, I did set out early as I had hoped to do and headed west toward Columbus, Ohio. I hit Zanesville, Ohio – a town about 50 miles east of Columbus – about noon and found Adornetto’s, a pizza restaurant I remembered from my undergrad days at nearby Muskingum College. (It’s now Muskingum University, but that phrase doesn’t come off my lips very easily.) I ordered a pizza to go and as I waited for it, the after-church crowd began to pack the place. Had I arrived just 15 minutes later than I had, my order would have been backed up in the kitchen. There was a threat of thunderstorms that afternoon, so I wanted to get to the Olentangy River Trail in time to ride before it got too wet to. Did it! I found my way off I-70 to the edge of the Ohio State campus by the river. Parked my car, set up my bike, and hit the trail.

In the six years since I had been to Columbus, the trail had lengthened in my mind. I was figuring on something like 13 miles each way, which I could do in a little over two hours and still get to my campsite in Indiana in time for dinner. Thirteen miles, in reality, was closer to the round-trip distance than to one way, to my surprise. But I enjoyed my hour or so of riding and sweating in the hot and humid Ohio afternoon. Just after I got back to my car, a shower erupted. But I made it to Whitewater Memorial State Park south of Richmond, Indiana, (about 100 miles away) in time to set up camp and cook dinner before dark.

As I was sitting by my campfire later, it began to rain so I hastily threw my food and one box of kitchen gear in my car and covered the rest with a tarp and crawled inside my tent. It rained on and off all night, and in the morning I discovered that I’d had a visitor in spite of the weather. My covered-up stuff had been gone into, and while nothing appeared to have been taken, there was considerable rearranging. A raccoon, of course, which theory was confirmed the next night when the critter showed up again, this time while I was getting my dinner ready. Bold it was, so much so that my shouting at it and clapping my hands did not scare it away. I began chucking rocks at it, and even that didn’t faze the raccoon. I didn’t think I could actually hit it with a rock, but I was beginning to wonder what it would take to drive the creature away when it decided to try its luck at someone else’s campsite. As to the ride on the Cardinal Greenway Trail on Monday, the day after I arrived at the park, it was good, but not great. Sunny day, nice Midwestern farm scenes, and more corn than I thought it was possible to grow.

But it was mostly the same scenery, mile after mile. The part of the trail near Richmond, though, did feature this tunnel that was more like a sewer pipe than a railroad tunnel.

I rode about 20 miles to the north, stopping near the town of Williamsburg before returning.

According to my map, the Cardinal Greenway Trail ran as far as the city of Muncie, and it had been my intention to ride from my Monday ending point north to Muncie on the second day in Indiana. But I decided the Cardinal Greenway had showed me what it had to show and so on Tuesday morning, I broke camp and headed to Illinois. It wound up taking most of the day to drive the nearly 300 miles from the Indiana park to the Illinois park where I’d booked, and so I set up camp, cooked my dinner, sat by the fire, and went to bed. In that order.

I had reserved a campsite at Jubilee College State Park, just west of Peoria and what looked like an hour’s drive from Normal. There was no sign of a college, past or present, from what I could see, but a young man in a store in Peoria told me “Some strange stuff goes on up there.” I heard this when I had a second night to stay there, so I didn’t inquire further. That Tuesday morning, I found the trailhead for the Rock Island Trail in suburban Peoria. It looked like the start of the trail, extending out of a strip mall parking lot. But as I was setting up my bike, I saw cyclists, dressed for trail riding, coming down the street from the other direction. I stopped one of them and asked, and he told me the trail, on the other side of the highway, went to downtown Peoria. I thought I’d check that out, and after some poking around in the neighborhood streets I found the (paved) trail and started riding south. After a couple of miles, though, the trail seemed to end at another highway, so instead of tracing it further I turned around. Soon I noticed that my bike computer was not registering speed or miles traveled. I stopped and made the usual checks, but nothing seemed wrong. Then I realized the problem might well be the battery, which had never been changed. I had become obsessive about miles ridden, and so I wanted to try to replace the battery. At first I thought I’d find a store in some small town along the trail, but that was uncertain. So I decided to put my bike back on the rooftop carrier and drive in search of a chain drugstore or the like where I could buy a new battery. Sure enough, just about half a mile down the highway there was a Walgreen’s. Into the parking lot I pulled, then I thought the Walgreen’s may not have the kind of specialized battery my computer needed. I was prepared to be disappointed and stymied when, exiting my car, I saw a store called “Batteries and Bulbs.” What luck! It was kind of like Radio Shack inside: clean and neat, with three guys in identical red shirts all eager to help the customer. One of them tested my battery, pronounced it dead, and came up with a replacement. He’s the one who told me about the “strange stuff” at the park, but what I thought was strange was the sudden appearance of exactly the kind of store I needed.

Back at the trailhead, I popped the new battery into my computer and was ready to ride. One problem: with the battery removed, the computer had reset to zero and to set it up again I needed to know the right setting based on the width of my tire and the diameter of the wheel. I knew those, but not the computer setting that corresponded to them. So I had to guess, and I hadn’t ridden too far before I realized that the mileage being recorded was not accurate. So I reset the computer again, this time guessing at another setting. This was closer to correct, but still not exact. With one more adjustment, I matched the odometer reading against the mileage markers along the trail and saw that I was close enough to being accurate that it would be good enough for me.

The scenery was not that much different from Indiana, but stretches of the old railbed did run through lines of trees on either side so that I wasn’t looking at corn stalks all day long. Riding along, I was trying to remember the words to Leadbelly’s great song “The Rock Island Line,” but I wasn’t doing too well. At the trail’s information station in the town of Wyoming, though, there was this historical marker that quoted from it. Cool!

Here was another instance of act-suffer-learn playing out. Rather than have my day’s ride – and the rest of the trip – wrecked because the bike computer wasn’t working, I tried to solve the problem. I believed I could solve the problem, and I did. Suffer? A little: I lost about 45 minutes of riding time with my battery search and I had my mind slightly disturbed by the battery store clerk’s remark about the park where I was camping. But it turned out fine. I learned that I could actually solve a problem on the fly (also that I should have had the manual for the computer with me, not sitting at home on my desk; that would have taken the guesswork out of resetting the computer for my wheel and tire.) As someone who is easily frustrated by mechanical problems, I was enjoying the glow of “problem solved” without any cursing or hair-pulling. And as someone who is relentlessly self-critical, it was nice to spend some time in satisfaction of what I had done.

The next day I broke camp and drove north into Stark County and picked up the RIT where I’d left it the day before.

The trail got more scenic as I went north, although it was hazardously pocked with gopher holes. I had to watch the trail surface carefully to avoid hitting one of those holes and crashing. That detracted a bit from my enjoyment of the scenery in east-central Illinois, but it was a nice day and now that I better knew the chorus to “Rock Island Line” I pedaled along singing it to myself.

At about 16 miles from where I’d started, the trail crossed the Spoon River. Then it ended, contrary to my map, with a washout at a creek. There was nothing to do but ride on back to the Spoon River bridge, eat my lunch, and shoot some video. So far, this was the prettiest part of my exploration of the Illinois and Indiana trails. My only regret was not offering a shout-out to Edgar Lee Masters, the author of Spoon River Anthology.

Back at my car, I loaded my bike on the roof and drove southeast to Normal. Checked in at the conference and found the dorm I would stay in for the next three nights. Turns out I was assigned to a suite: three bedrooms and a shared bathroom. OK. I unpacked and went to take a shower. In the bathroom I found a little toilet kit resting on the shelf above the sinks. I assumed it had been left there by another person in the suite, and I felt a feminine vibe from it, perhaps because it was half clear plastic and half orange flower pattern. Still, it could have been anyone’s. Downstairs at the desk, I inquired as to who else was booked into the suite. The clerk showed me the registration list, which showed initials and a surname for suite 16A, where I was also staying. The initials “C.B.” hid the gender of my suitemate, and I did not recognize the surname. Now doubting that the housing bureau at Illinois State U. would mix genders in a suite, I left for the conference’s opening reception still not knowing anything about who I was sharing the suite with except that they had a toilet kit with orange flowers on it. After dinner when I came back to the dorm, I met a woman in the suite. She told me her name was Cynthia, but I could call her Cindy or CB. She presented as a woman and her formal first name and its diminutive said “female.” So there went my assumption about gender segregation. I never had a chance to call her anything, though, because I never saw her again throughout the conference.

Saturday evening at WPA there is an outing sponsored by a textbook publisher. I had some time between when the busses left for the Bloomington Zoo and the close of the last afternoon session, and I had noticed from my sixteenth-floor window cyclists and pedestrians using a marked crossing at a street a block or two away. I checked the local map and saw that there was indeed a trail that ran north-south through Normal and into Bloomington. I figured I had time to get in maybe an hour’s ride and still catch the bus to the outing. So I dressed out, got my bike off my car, and rode off to find the trail, the Constitution Trail, as it is named. Had a pleasant, easy ride on which I also learned that in the early 1850s, Abraham Lincoln was just another lawyer suing a municipality on behalf of a wealthy client. The historical marker says Lincoln “represented the Illinois Central [Railroad} in its successful attempt to avoid paying taxes to McLean County. When Lincoln later took the IC to court to collect his fee, it was said to be the largest yet collected by an American lawyer.”

This day reversed the last two parts of the act-suffer-learn paradigm, sort of. I’d acted on impulse to ride the trail; then I learned something about A. Lincoln’s early professional days. Then I suffered. Riding back to Normal, I took a wrong turn on what turned out to be a network of trails in that city, not the up-and-back-only trail I thought I was riding. Thinking that this ride was challenging the phenomenon that the way back is always shorter than the way out, I churned on with increasing speed and urgency as my time to shower, change, and catch the bus to the outing was getting tighter and tighter. After about 15 minutes of hard riding – at least three miles of trail – I figured out I was way off from where I started. Nothing to do but retrace my ride to where I’d turned wrong and get on back to my car. I did that, but the result was I’d missed the bus to the zoo. I wanted to see it, so I drove my car the couple of miles to Bloomington (home of Illinois Wesleyan College, co-host for the conference). I picked up my box lunch/dinner and ate it seated on a bench across from the bald eagle enclosure. Birds were screaming at each other about something, so they seemed a little less dignified than how they are usually depicted. Some of my conference buddies came along and chastised me for being late. They got on the bus back to Normal and I had to drive myself back. That action did, however, lead me to stroking a ball python in the gift shop; it turned out that I was the only zoo-goer that evening who actually touched a wild animal: act-suffer-learn.

I left Normal, Ill., Sunday morning July 20, heading home. No camping on this leg of the trip: I would spring for a motel somewhere in Ohio, I supposed, and get home Monday. At this point, with the unplanned rides on the GAP and Normal trails, I had ridden close to 75 miles. Good enough, even if I’d found the Midwest trails not as interesting as those near my home. Act-suffer-learn. I did land in a motel near Akron, Ohio, that night as I took I-80 east. Got an early enough start Monday that I was in western Pennsylvania by noon. I thought I might have time for another unplanned ride if I could find a trail not too far off the highway. My Pennsylvania trails guide showed me that the Sandy Creek Trail in Venango County was handy enough to the interstate. Indeed I found the trailhead and followed the trail west.

No stoners along this trail, but the scenery was well worth the detour.

Especially when, returning across a trestle, I came upon a young porcupine that was getting ready to bungie-dive off the bridge. Odd place to see a porcupine, but it was cool to get close to it.

I rode for a little over an hour – about 15 miles – and got back to my car knowing I’d still get back home before dark. Pleased with myself, I bopped along I-80 singing along with my cd-player and basking in the glow of a successful trip all the way around. The basking stopped when cockiness took over. I tried to pass a tractor-trailer at a place where the left lane was narrowing to a close. Bad judgment. The trucker gave me no room and rather than collide with the trailer, I chose to collide with a reflective marker on the left. Not an enormous crash, but enough to tear the trim loose around my left front wheel well and smash in the corner of the front bumper. This was suffering, resulting from my rashness and my adrenaline. What did I learn? Well, the obvious: passing a truck in such circumstances was foolish. But more when I got home. Within minutes of my arrival, somehow, my wife knew something had gone wrong. I knew I’d have to tell her about the mishap, but I wasn’t prepared to tell her right at the moment. But I did. And I suffered the consequences. She ripped me up one side and down the other when I said I had not reported the accident to our insurance company. So I’d committed two bad errors: driving like a fool and then minimizing the incident enough that I never thought I should report it to my insurance. Being the depressed person I am, I plunged into emotional darkness for that night and the next day. Moreover, I had forfeited whatever chance I’d had to share some of my adventures with my wife. Not that she’d be dazzled by my narrative, but still the trip had been fun and successful for the most part. Too bad getting lost on the Normal-Bloomington trail wasn’t the worst of it.

I’ll try to end this on a more positive note – with a video of riding through a tunnel on the Sandy Creek Trail. If you listen carefully, you can hear me observe something about “act-suffer-learn”: that “It’s the surprises that make travel the most fun and interesting.”

Biking — A Sidebar

Of course I’ve had a bicycle since I was 12 years old, but biking became a more serious avocation for me late in the 20th century. About that time, a college friend, Dennis Berry, with whom I’d reconnected and who was a serious cyclist, suggested the two of us ride across the U.S. when we turned 60. That would have been 2006. No way I could have done that when the idea was first floated, but thinking it might happen, however unlikely, I started riding seriously myself. I wasn’t climbing mountains or jumping bolders; just riding, mostly, nearby trails. Dennis and I never did make that ride. For one thing, not only was I teaching full-time, but I had year-round administrative responsibilities that kept me busy summers. So I would have had to take a sabbatical to have six weeks free for a cross-country jaunt. Wasn’t going to happen. But it really didn’t matter because I became a trail-riding junkie, starting about 2004.

My bikes

Living in Tidewater, Virginia, in the early 70s, I bought my first good bike. It was a Coventry Eagle, a brand made by the English manufacturer Raleigh. It was a road bike, yellow. Pretty cool. (Too bad I have no photographic record of it.) I was able to ride it out to the Portsmouth campus of Tidewater Community College, just a mile or two from where I was living. That campus sprawled over many rural acres and, as I recall, there were trails. In 1974, I moved to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and met a couple of fellow grad students who liked to race (sort of) along the River Road just west of the LSU campus. I would join them sometimes, although they did make fun of my no-name bike. I also used the bike to commute to campus from my apartment. I did have a car, but gas was expensive and I had very little money. So that worked out.

Ater grad school, that bike moved with me to teaching jobs in Nebraska and Pennsylvania, by which time it was ten years old and showing some wear. Neighbors tipped my wife and I to a local place that assembled bikes and sold them cheap. Each of us bought one; mine was a mountain bike. I did use it occasionally to commute the couple of miles to my workplace, and I took a few trail rides on it but nothing really serious. I’m thinking I had that bike for eight to ten years. Again, no photographic evidence. (As an aside, this was before cell phones came into vogue — or at least before I had a cell phone myself. So no pix.)

For a Christmas gift in 2002 or ’03, my wife gave me a gift certificate for what was at the time the premier bike shop in our area. I bought a really nice Cannondale hybrid mountain bike from that shop. It seems like a different lifetime now, but I would rack up 2000 miles or more each year, riding from March/April to November, three or four times a week. I think I topped out at 3350 miles one year. This photo of my odomoter is from 2020, the last year that I cracked 1000 miles.

I also made the camping/cyling adventures I have written about and posted elsewhere on this site. And after 2008, when I got into multi-modal composition, I made lots of videos of my biking. So there are pictures.

Here is my Cannondale, pictured during my trip to the Midwest in July 2014. By that time, it had thousands of miles on it and some of it was held together by duct tape!

Come spring of 2015, I took this bike to a local bike shop for its annual preseason tune up. Dude told me I might as well buy a new bike, for what it was going to cost me to get the Cannondale ride-ready. Not what I wanted to hear! The shop where I’d bought it was, I thought, a little snobby, but I wanted another Cannondale; it was the best bike I’d ever owned, and I had ridden thousands of miles on it — without taking it cross-country on roads. A web search showed me of another bike shop in a nearby town that offered Cannondales. To it I went — and wound up buying this Giant Roam, another kind of hybrid mountain-road bike. The guy at the shop told me Cannondale no long made a bike like mine, and this Giant was the closest thing to it I could get. This bike had 28-inch wheels, vs. the 26-inchers on the Cannondale, so the frame was bigger too. It had 27 speeds, as opposed to the 18 on the Cannondale. It also had disc brakes, new to me but really efficient. And the overall look of it was sharp, making my old Cannondale “Comfort 400” model look stodgy. So as of the 2015 season, I was rocking and rolling on this Giant “Roam 2.”

In July 2016, I drove up to Maine to hang out with my oldest brother. I was not planning to ride, so I left my bike for maintenance at the shop where I’d bought it. I did bring my tent and camping gear along, and planned to spend one night each in the White Mountains of New Hampshire and the Catskills of New York. A thunderstorm came down on me at my N.H. campsite. I stayed dry enough, but my tent and ground cloth got pretty muddy. I decided to find a motel for the next night, and save the Catskills camping for another day. When I got back home, I had to spread my gear out in the backyard to wash it down and dry it. At the same time, we had a home security technician at the house upgrading our alarm system. Thinking everything was secure while he was working (and my wife was at work at her job) I went out on an errand. While I was gone, the security guy stole my bike, right out of my garage! Jerk! Of course I did not suspect him; thought some pedestrian passing the house had seen it in the garage and snatched it. But about a month later, my wife saw the security guy at a Wawa store and approached him. She said, “You know, it’s funny, but when you were working at our house my husband’s bike was taken from our garage.” His reply fingered him: “Well, I never could have got it into my work van.” Maybe he didn’t; maybe he did. Or maybe he called a friend who had a less crowded van and they stole it together. Whatever the case, I was now almost bikeless. Almost, because I still had the old Cannondale, which I was using on our annual beach vacation. (I had taken the new Giant one time, and got sand in the brakes, making them shriek like a banshee when I put them on.) At this point, my old Cannondale was held together by chewing gum and duct tape, but for two weeks at the beach it was good enough.

Nevertheless, I hustled down to the shop where I bought my Giant, wanting a replacement right away. Nothing in stock, I was told; between model years. I ordered a new Giant Roam, but wouldn’t get it for about six weeks. So I brought my Cannondale in — in such bad shape, I had been told, that it would cost a lot to make it rideworthy — and they fixed it up for, like, $75. I rode it until the new Giant came in.

I rode that bike from 2016 to 2023, logging thousands of miles. It was great. Except that my body was shrinking at the time. The hormone therapy I was taking for my prostate cancer caused, among other side-effects, the slow weakening of my bones, particularly in my spine. Collapsing vertebrae cost me at least 4 inches of height! Galling, inasmuch as I had thought of myself as “tall” since I was 17. It also weakened my back. The way I had been storing whatever bike I had was to hang it upside down by the wheels on hooks attached to the roof of my garage. To store it, I had to do a kind of “clean-and-jerk” maneuver with the bike: first lifting and turning it so the wheels would be up, then heaving it overhead and catching the wheels on the hooks. This had been hard enough whenever I came back from a ride, but as of 2021 I had serious trouble making this maneuver. If I did clean-and-jerk it OK, I would have trouble holding the bike steady overhead to get the wheels on the hooks. One time, I lost my balance and fell backwards on the concrete garage floor with the 30-something-pound bike on my chest. More spinal injuries, though nothing so badly broken that I was crippled. But this arrangement simply had no future. (Maybe I should add that we have a single-car garage, so if I want the bike sheltered from the elements and want to store a car in the garage, the only place for it is hanging from the ceiling.) I struggled throughout the 2022 and 2023 seasons. Getting ready for ’24, I made an appointment with my mechanic — to have both the Giant and the Cannondale tuned up for the season. He sensibly asked me if I was uncertain about riding the Giant why I wanted to put the money into a tune-up. Good point. So I sold it and have been riding the past two seasons exclusively on my old Cannondale. The “old” part of it now is the frame; everything else is new: gearing and braking systems, handlebar, pedals, wheels. It still has “Comfort 400” stenciled on the top tube, but it no longer has some of the “comfort” features, namely the shocks under the saddle and on the rear wheel and the wide, padded saddle. But it is still a great bike, maybe even better than it was when I bought it. Here it is, from the summer of 2025.

I also bought a storage system that works by pulleys. No more clean-and-jerk; no more staggering with a 37-pound standing shoulder press.

Trails

I prefer trails: no vehicular traffic, mostly level, and usually out in nature somewhere. Even if the mythical cross-country ride was to be done on highways, once I moved from a road bike to a mountain bike, I did my practicing on trails. Before I started riding religiously, I didn’t know there were so many great trails near my house in Bethlehem, PA (where “near” means within an hour’s drive). In this section, I’ll briefly discuss some trails near where I live and include links to their websites.

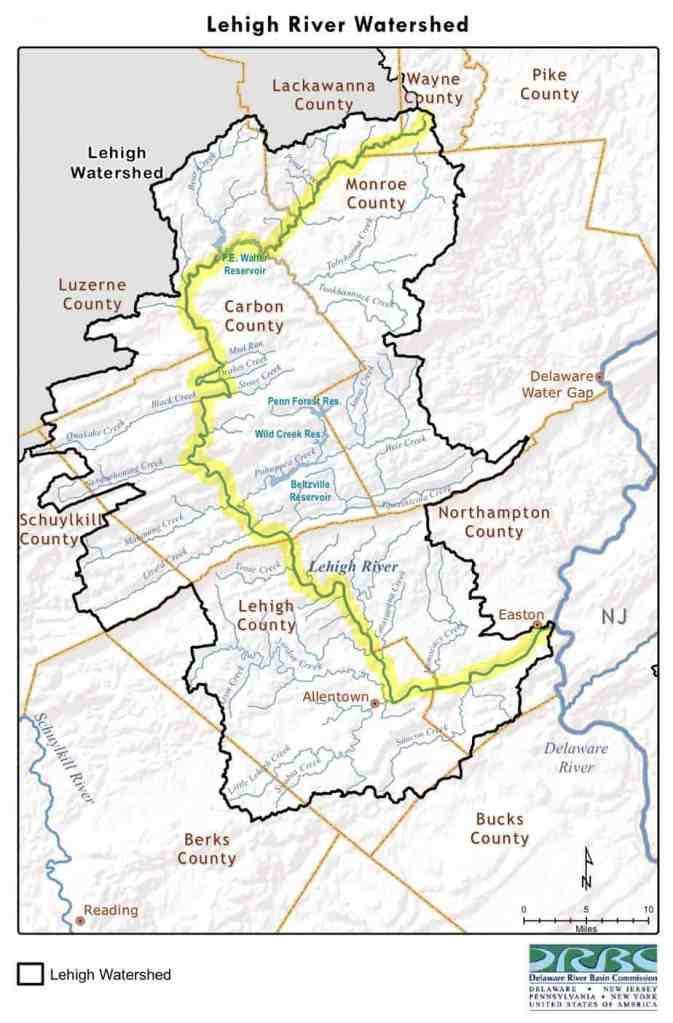

Bethlehem is in the Lehigh Valley, so named because the Lehigh River is the dominant geographical feature. The Lehigh rises in the Poconos in northeast Pennsylvania and flows 109 miles to where it empties into the Delaware River at Easton, 12 miles east of Bethlehem.

The D&L Trail —

In the early 19th century, canals were dug along the Lehigh upriver from Easton and along the Delaware upriver from Philadelphia. That part of the Delaware and all of the Lehigh are too shallow for big boat traffic, so canals were the way to, basically, send coal from the Poconos to Philadelphia and manufactured goods from Philly up to the Poconos. The canal towpaths where mules once pulled the boats have been repurposed as recreational trails. They connect to rails-to-trails upriver from the town of Jim Thorpe in the southern Poconos, making altogether the 165-mile-long Delaware and Lehigh Trail, from Bristol, Bucks Co., to Wilkes-Barre, Luzerne Co.

As the Lehigh River flows through Bethelehem, the trail runs beside it. I’ve not ridden the length of the D&L, but I have ridden much of it at various times from Lumberville, Bucks Co., along the Delaware (mile marker 31), to past White Haven, Luzerne Co. (mile marker 140), along the Lehigh.

Two or three miles north of White Haven, the trail diverges from the Lehigh and becomes, for me, scenically less interesting. So I have covered about 100 miles of the D&L. Because the trail is so long, segments of it are known by local names: “The Lehigh Canal,” “The Delaware Canal,” “The Lehigh Gorge,” etc.

The portion of the trail that runs from Weissport, Carbon Co., northwards to White Haven, Luzerne Co., offers the most dramatic scenery: the Lehigh Gorge. A few years ago, a bridge was erected across the Lehigh River at Jim Thorpe that effective lengthened the available rides through the woodsiest parts. The town of Jim Thorpe is often crowded on weekends and in summer, but before the contruction of the bridge, if I wanted to ride through the Gorge, I’d have to start in Jim Thorpe itself or in the state park at Glen Onoko, which is about five miles upriver.

With the bridge in place, I can ride into the Gorge from virtually anywhere below it. One trailhead is in Weissport, a dinky town near the hicktown of Lehighton. That stretch of trail has been upgraded from Weissport to the bridge at Jim Thorpe and it affords some stunning views of the cliffs and the river. The D&L Trail runs along the west bank of the Lehigh River from Cementon up to Lehighton; to continue on the trail, it is necessary to ride to the east bank on a road bridge (although with designated bike lanes) and through the center of Weissport. Here’s that town bragging on its dominant culture one summer afternoon:

Weissport offers nothing else except a trailhead less busy than Glen Onoko or Jim Thorpe.

The “Cement Belt Trail” —

But there are some other nearby rails-to-trails with which I am familiar. Among them is the short (six miles one-way) Nor-Bath Trail (so named because its terminal points are near the boroughs of Northampton on the west and Bath on the east). From Northampton, it is possible to connect to the D&L on the west bank of the Lehigh River and ride north … a long way; it is also possible to connect with the Ironton Rail Trail, which runs away from the river to the west, connecting Northampton with the little place called Ironton.

https://norcoparks.recdesk.com/Community/Facility/Detail?facilityId=18

https://www.irontonrailtrail.org/map.html

My name for the connected NorBath and Ironton trails is the “Cement Belt Trail” because both those old railroads serviced the cement industry in the Lehigh Valley. Here are a couple of views: near the east end of the NorBath, a relic of the cement industry, and a handcart along the Ironton Trail.

The Saucon Rail Trail/The Upper Bucks Trail —

There’s also the combined Saucon Rail Trail and Upper Bucks Trail, which together run about 12 miles.

https://www.montgomerycountypa.gov/DocumentCenter/View/3458/Perkiomen-Trail-Brochure-June-2024

Before the connection was made, the Saucon trail was only about 7 miles long. It is also wide, well-groomed, and runs for several miles through affluent neighborhoods in the affluent Lower Saucon Township. The scenery is OK, especially where the trail skirts the championship Saucon Valley Country Club golf course, but the trail can be a little too crowded for me sometimes. The development of the Upper Bucks Trail, short though it is, allows for about a 20-mile ride, round-trip, with the few miles on the UBT offering more rural and woodsy scenery.

The Perkiomen Trail —

https://www.montgomerycountypa.gov/DocumentCenter/View/3458/Perkiomen-Trail-Brochure-June-2024

The “Perky” is an interesting and challenging trail. Going southward, it follows the Perkiomen Creek through Montgomery Co., from Green Lane Park to a place called Oaks, where it connects to the Schuylkill River Trail. That trail goes on down to the Art Museum in Philadelphia. The Perkiomen Trail passes the site of the Philadelphia Folk Festival near Schwenksville, goes beside the grounds of Graterford State Penitentiary, runs through the town of Collegeville, and includes the hyper-challenging Spring Mount Hill. A sign at the bottom of the hill on the north side warns, “12 percent grade; 1/4 mile.” When I was younger, I sometimes succeeded in climbing it; some other times, I had to dismount and push. Lately, when I think about driving to that trail for a ride, I hesitate to follow through because I know I won’t be able to make that climb.

Trailheads and trail scenery

As I age (now closing in on 80), of course I am weaker all the way around. By some lights, I should be riding a recumbent bike or a motor-assisted one. Not yet, if ever. Without buying a trailer hitch for my car and a rear carrier, I couldn’t manage toting a bike like one of those to the trail. For the moment, I say I will never ride a power-assisted bike, even though two cyclists I respect have them. But as long as I can mount, pedal, and dismount my 26″ Cannondale I’m staying with it. Snob confession: whenever I see someone on the trail riding a power bike, I try to ignore them (although I do mutter “ride a real bike!” under my breath.) OK, those kinds of bikes do allow people who might not otherwise be biking to get out in nature and ride. That’s a good thing. But the trails I ride are mostly level, and the occasional climb is manageable, if not easy, on my leg-propelled bike. I don’t have to go 20 mph to have fun, and even if I did, there would be the expense of buying a new carrying rig for my car. I’ll die first.

I won’t get into a long discourse on “act-suffer-learn” in this sidebar, but I will say that paradigm is instantiated every time I go out for a ride — even if it’s peaceful and without incident. It has to be, because to go for a ride is to act, and whatever happens on the ride is some kind of suffering (sweating, shortness of breath, falling, or any kind of discomfort). Learning is variable; maybe it’s just making a mental note of hazards on the trail or appreciating the natural beauty through which I ride — like finding this nice little rock outcropping above the Lehigh River:

Or riding past the Nockamixon Cliffs along the Delaware River on a fall day:

Or coming across animals in their own environment. At a place in the Lehigh Gorge known as Penn Haven Junction, I found this handsome black snake slaloming through the links of a fence as a way to shed its skin. Yo!

Big Blue Herons are among the fabulous birds I’ve seen along the trail. This one was checking out the Delaware Canal at low water.

And the occasional snapping turtle looks like it just crawled out from pre-history!

Long as it is and close to my home, the D&L, or some portion of it, is my go-to trail. Here’s a short clip I made riding through the woods beside the Lehigh River on an autumn day and stopping at a little rest spot. Maybe you can get an idea of how nice it is:

Most of the trail along the Delaware runs atop a levee that separates the canal from the river. Being a century old, though, the levee is fragile. At the moment, there are enough breaches in it that the canal has been drained until the repairs are finished. The scene below is of a breach caused by water rushing through an early 19th-century culvert that burst and compromised the levee. The breach is visible between the barricades. When the canal is full, this is ride is even better. Perhaps by next season it will be.

Most of my rides are done in shuttle fashion: out and back. But there is a loop ride I like. It’s about 23 miles roundtrip from the wonderfully named town of Upper Black Eddy on the Delaware down the Pennsylvania side to Lumberville, where a pedestrian bridge crosses the river to Bull Island State Park in New Jersey and up the Jersey side to Frenchtown, where there’s a road bridge back to PA.

For years, I interpreted the term “trailhead” to mean the end point of whatever trail; I called places along a trail where you can get on “access points.” Eventually, I’ve learned to call any point of access to a trail a trailhead, which is the common sense of the word even if metaphorically wrong. So every trail is a multi-headed beast, and you start your ride wherever is convenient. My favorite trailhead for the long D&L is at Hugh Moore Park in Easton. When I first started trail riding earlier in this century, the park was pretty derelict, but — and I am assuming here — the federal grant that created the “Delaware and Lehigh National Heritage Corridor” enabled not only improvements to the trail but the spiffing up of Hugh Moore Park. In any case, it’s a good starting point for a ride: from there I can ride across the Lehigh on a road bridge with a dedicated bike lane and continue on westward/northward along the Lehigh Canal Trail portion or I can stay on the south bank of the river and take it to downtown Easton where the Lehigh flows into the Delaware. For a little fun with rhetoric, I invite a little foray into semiotics, the study of signs and there meaning. All kinds of signs, of course, but actual informational signs as well. In the photos below from Hugh Moore Park, we have two signifiers referring differently to the same signified. Alas one of the signs has now been replaced, so the fun confusion is no longer available — except in memory.

Incidents, accidents, and encounters

If you bike, you are going to fall. Maybe not every time out, but enough to make it a hazard. Of course I would never ride without a helmet, but in the past few years I have been taking blood thinners. So even a “light” fall can result in copious bleeding. When I first started on these, and told my cardiologist what I did for recreation, he said to me “Try not to fall,” as if otherwise I would. Yeah, right. The day before Thanksgiving in 2022, I went out for a ride on the Cement Belt Trail. I wasn’t looking for a long ride, just a shortie to cap off the year. As I was going through a gate at a road crossing, I fell, slowly and lightly, to my left. Couldn’t get my foot out of the toe clip fast enough to plant it on the ground, so over I went, catching my left wrist between my hip and the ground. I knew right away it was broken. In all the falls I’ve had — and some of them bad — I had never broken a bone. Thank you osteoporosis! Yes, that is my arm in that cast.

Along the Delaware Canal, there are spillways that allow excess water from the canal to flow into the river. Some of these have footbridges that give the user an option to dealing with water — when there is water in the canal, which is not a given.

Where the water leaves the canal, as in the video above, there’s a section of concrete on the trail. At one such place, where no footbridge is involved, it takes some derring-do to ride across it. Even though the water in the spillway is only a few inches deep, I developed a strategy to cross it without soaking my shoes and socks. I’d get up a head of steam and just before I hit the concrete section I’d lift my feet off the pedals and tuck them up behind me — which means I’d be freewheeling. This was thrilling and fun.

But Labor Day weekend 2020, riding my Giant, with had narrower tires than those on my Cannondale, the force of the water swept the bike out from under me. Down I went, splat! The water cushioned me from breaking a bone, but I landed on the bike and it beat me up a little on my left hand and leg.

That too was thrilling, but definitely not fun!

Another time: August 2018; it had been a rainy summer. There were puddles on the trail, especially in a stretch full of potholes. Zipping along heedless, I tried to skirt a puddle but caught the wet grass at the edge of the trail and fell down the canal bank into a couple of feet of water. With the help of some passersby, I dragged my bike up out of the canal. It was damaged, but my Bob Brien, my fave bike mechanic, saved it. He was most concerned that water had gotten inside the tubing, so the bike had to be disassembled and dried out. Successful, which earned Bob the title of “bike whisperer.” My cellphone, however, did not survive the dunking. Here’s a shot of the canal, dry, about where I went in. You can get an idea of how steep the banks are at this point.

Another fall — involving me only as a spectator — was in 2017 when, riding along the Lehigh near Easton, I saw a tow truck come down from the nearby road and disappear down the trail beside the river. That was a first. When I came upon the stopped truck I saw the driver’s objective: a car lying on its driver’s side just off the trail in the river. That was scary. The tow truck driver said a motorist unfamiliar with the area had been led off the road to the trail by his gps. The unlucky driver got as far as the road bridge that crosses the river from downtown Easton, where the overhead clearance is too low for even a small car to get through. So the driver reversed the car up the narrow trail to a slightly wider spot where they tried to turn around. Bad move: the car slipped off the bank and into the water. In this video, I am riding upriver from Easton, beneath the road bridge and along the narrow, if paved, trail. The spot where the video ends, just beyond where the wall slopes down to meet the trail, is about where the car fell into the river. The tow truck guy said the driver was able to climb out through the passenger side window and wade ashore. Good enough, but I hope I never see the like again.

Often I encounter other people, especially other cyclists, on the trail. Usually these meetings are routine, nothing to write home about. But not always. One time, riding along the D&L Trail east of Bethlehem, a cyclist passed me at a narrow spot, on the right, with no warning that he was there. He was really hustling and was quickly out of sight. After a couple of miles, though, I drew within view of him. I challenged myself to see if I could catch up with him. I wasn’t angry, just stimulated. I cranked the Giant up to about 15 mph and came up behind him at a point where the trail divides around a tree. He went left; I went right and with a bit more acceleration got in front of him. I rode maybe another half mile when I heard something to my rear and, thinking something had fallen, I braked. Disc brakes, remember. The other rider just about climbed my back, he was that close to me. He was cool, though, and said, “Hey, bro! What’s up?!” I explained why I’d stopped, and he launched into his biography. His name was Angel. He’d been a bike messenger in New York City and was riding the bike he’d used for that gig. He said he’d moved to Bethlehem and had an apartment in the “pre-historic district.” He showed me how his machine was geared in such a way that “You can’t catch this bike.” All right. Then he hopped back on his saddle and sped away. After another while, I came close to him again. I was just about to pass him and say “That’s twice!” when he stopped and smiled. “You want to get a beer?” he asked. “Sure,” I said, and we rode together to the bar in a seedy hotel in the worn-out nearby village of Freemansburg. He bought me a beer; I bought him one. Then he goes, “You want to smoke a blunt?” “Sure,” I said again. We left the bar and went on across the trail to a secluded spot by the river. He rolled one up and we toked on it. At this point, another dude appeared. He too was Latino and knew Angel. They discussed a fertile fishing spot nearby, then I thought it was time to move on. But Jose (as he called himself, stammering) told me that if I ever wanted some weed from the Marvine (public housing in Bethelehem, not far from Freemansburg), I should just ask for Jose, “the guy who talks funny.”

Thanksgiving weekend one year (2013?) was unseasonably mild, so I went on down to the Perkiomen Trail, feeling strong enough to challenge the notorious Spring Mount Hill. One of the tricky features of that climb is that you get about 100 yards up and think you’re doing well, when the trail bends and gets much steeper. I confess I’ve never figured out how to best run through the gears on that climb. This particular time, I was trying to shift to my lowest gear when the chain popped off the cassette and got wedged tight between the caassette and the crank on that side. Could not get it loose! But here’s something I’ve learned about some fellow trail-riders: if they see you broken down, they’ll stop and offer to help — most of the time. (I do the same, and I carry a few tools on my bike in case they’re needed.) So it’s getting late on a November afternoon, however mild, and I am in an out-of-the-way place. Another rider comes along and tries to pry the chain on my bike out of the vise it has got stuck in. It looks like he’s not going to succeed. I pick up my cell phone and call my wife. I’m going to have to beg her to drive to a place nearly an hour from home to which she’s never been so she can take me to my car, which I can then drive at least close to my stranded bike and carry it home. The whole project is fraught! But just as I’m starting to give her directions, the other cyclist pops the chain loose. I can reset it on the gear cassette and be on my way. I never did get his name.

More recently — Labor Day weekend of this year — I head up the D&L where the trail runs about nine miles from the Cementon trailhead to the small town of Slatington. This portion of trail is through woods along the Lehigh R., with very few access points. On this day, eighteen miles r/t will get me to 300 miles for the year — dinky but at least it’s a round number. I make it to the Slatington trailhead, take a break, eat my little snack and hop back in the saddle to ride the return leg. I go about five miles when I notice my front tire is going flat. That makes the bike hard to steer, and if I do try to continue riding, I’m afraid, I’m going to destroy the tire and wheel. It’s also hard to push the bike with a flat tire, so I have to tip the handlebar up and roll the bike along on the rear wheel. This probably sounds a lot easier than doing it is. But I’m trundling along, hikers and cyclists passing me in both directions. One group stops to offer help, but just at the moment when I am again calling my wife to drive up to the closest trailhead and ferry me to my car. So I have to wave these folks off. Other passersby cluck in sympathy or try to make jokes, but it’s all I can do to roll my bike along in this awkward position so that I can’t even respond to them. Then an old man (at least he looked older than me), long-haired, long-bearded, carrying a staff while he walks north stops to offer help. He’s so earnest that I have to give him some response, part one of which is “I don’t know what you could do,” and part two is “It’s taking all my stamina to push this bike; I don’t have the strength to even talk with you!” So he goes on his way and I go on mine. A bit later, he has turned around and approaches me from behind. He practically begs me to let him help. The only thing I can think of is to detach the front wheel and let him carry it while I continue the one-wheeled push I’ve been doing. This does help, because now there’s less weight on the front of my bike. Also, at this point I’m less than a mile from where my wife is waiting. She’s there, I lock my bike to a railing at the parking area, and get in her car to ride to mine, another four miles down the line. It all works out OK eventually and I return home fatigued and dirty. The old man, “Paul,” he said his name was, may have offered more moral support than physical, but he did offer, showing there are indeed some Samaritans out there.

Professor Wingard’s Conversion from Loyalty to Secession

https://www.thedaln.org/#/detail/1af338b6-3f6c-4724-9b31-9db1a0e3b4b9

The above link takes you to something I wrote in 2016 while I was teaching at Penn State-Abington. It describes my becoming literate in Writing Studies, after a career as a literature professor.

Mashup – What Is Writing in the 21st Century?

Cycling the Pine Creek Trail: The Rhetoric of Travel

“Act-Suffer-Learn”

My wife telling me “You’re too old to go off by yourself like that” was what clinched it for me. I had been discussing with her a plan to go on a four-day camping trip to remote north-central Pennsylvania, alone, and to bike the Pine Creek Trail, which runs about 63 miles from Wellsboro Junction, Tioga County, in the north to Jersey Shore, Lycoming County, in the south. I wanted to do this for several reasons: I had become a cycling junkie and was looking for someplace new to ride; I love tent camping; I wanted to prove something to myself — that I could manage such a solitary trip and come back in one piece, after having undergone a radical prostatectomy about six month earlier. Having this “adventure” experience was part of my LIVESTRONG mentality.

The Pine Creek Trail had caught my eye as I searched Pennsylvania rails-to-trails on the Web. I could get there in one day’s drive from my home in Bethlehem, Pa.; it was reportedly a well maintained and “easy” trail, rising a mere 2 degrees of elevation over its entire length; and it traversed some of the most beautiful scenery in the state.

My wife, Karla, and I had been negotiating back and forth about my going off somewhere alone. She was thinking about what could go wrong; I was thinking about what could go right. She finally relented, and off I went, camping gear, food, and firewood packed into my car and bicycle attached to the roof.

Trail riding is my “hobby,” my primary way of staying fit, and an important way in which I have fun. It started, really, in the first decade of this century. A college friend with whom I had reconnected after many years suggested that when the two of us turned 60 we should cycle across the country. I didn’t know if that would happen, but I did know that I would have to get into some kind of cycling shape in advance of any such trip. The cross-country excursion never did happen, but my “training” for it on my mountain bike consisted of me riding an average of 80 miles a week from March to November on trails close to home. By the summer of 2009, I was 62, recovering from cancer surgery, and a cycling junkie.

But I am also a rhetorician — I write, I teach writing, and I study and teach rhetoric. With that hat on, I had learned the notion that travel is a rhetorical act. This thanks to John Ramage’s book Rhetoric: A User’s Guide.

Ramage distinguishes among commuting, touring, and traveling. The first, in the rhetorical theory developed by Kenneth Burke, whom Ramage follows, is motion without action: moving almost automatically, without conscious thought as to purpose or the scene through which one moves. Touring includes purpose, so it is action, not just motion, but the purpose is to see and experience the known. Or the “preformed,” as Walker Percy calls it in his excellent essay “The Loss of the Creature.”

Even if you tour a place you have not been to before, the motive is to see what you expect to see: the Grand Canyon, for instance, or the Sistine Chapel ceiling. People go touring, in this sense, to have a prefabricated experience; their expectations are formed by guidebooks, travel brochures, and popular images. (Ironically, though, as Percy says, the tourist doesn’t see the “real” Grand Canyon; he sees a version of it mediated through other agencies: the Park Service, corporate travel agencies, planes and buses.)

Travel is also motion with purpose, but a more open-ended purpose: to have, or to be willing to have, an experience unlike, in some crucial way, any other; to encounter the strange in the sense of that which is out of one’s comfort zone. Travel is also a matter of identity formation. The tourist brings his identity with him and returns with it unchanged. The traveler finds or creates his identity in the process of traveling.

Now here, I have to digress. By “identity” I don’t mean to suggest that the traveler finds or discovers a pre-existing self that is the totality of his being. Rather, the traveler creates an identity as she travels — a partial identity, that is, who she is under these circumstances, not others.

This process may be a matter of “bringing out” something within the traveler that he didn’t realize was there, or it may be a matter of “becoming’ someone whom he was not before he traveled. In contrast with touring, travel can be, is, a risky business. Travel seen rhetorically involves what Ramage, following Burke, calls the “Act-Suffer-Learn” pattern. To go somewhere with the intention of encountering something “new” is to act. The action of traveling entails suffering, because, unlike touring, travel is open to contingency. That is, something unplanned and possibly inconvenient is likely to happen. And to recognize that suffering, to act upon it, is to learn, where the learning may be about the scene of one’s travels or the traveler herself.

Digressing a little further, I will add that to “suffer” is not necessarily to have pain. It is closer to “undergo” or “experience.” But the Buddhist notion of samsara is also relevant here: the suffering that is the ongoing condition of being human, not an enlightened being. Or if you prefer, it is existential reality.

So in late June 2009, I take myself up to north-central Pa. to travel the Pine Creek Trail. Much of roughly the northern third of the trail runs through “the Grand Canyon of Pennsylvania,” aka the Pine Creek Gorge, with mountainsides rising some 1,000 feet above the creek. Camped at Leonard Harrison State Park on the east rim of the Gorge, I can hear Pine Creek rushing far below and see the mist rising from the water.

But I cannot see the creek itself. For a view of the Gorge with both the creek and the trail that runs beside it, it is necessary to visit the state park on the west rim of the Gorge, Colton Point State Park.

Although campsites are available at both parks, I choose Leonard Harrison because it has hot showers and flush toilets, whereas Colton Point does not. In this respect, I am a tourist, not a traveler, because I don’t want any surprises where these kinds of amenities are concerned. On the other hand, I am a traveler because I am responsible for my own shelter and food; I will sleep in the tent I pitch and eat the food I prepare. And if anything “goes wrong” I will have to deal.

My plan is to ride the length of the Pine Creek Trail in three sections, shuttling over each. One day, I will start at or near the northern trailhead and ride approximately 21 miles south and back; the next day, I will drive to the first day’s turnaround point and ride about 21 miles south from there and back; the third day, I will cover the southernmost third of the trail, again by driving to the previous day’s turnaround point and riding from there. This is kind of clumsy, and it has me in my car for some time instead of on my bike, but it means I don’t have to pack my tent and everything with me each day. I will bring a lunch each day, though, and my video camera.

Videoing scenes along the trail may, I realize, move me from an authentic encounter with the trail and the creek to a mediated one. But I think that because I won’t be videoing all the time I’m riding and because I will keep on moving through whatever scene I am recording, I won’t be a mere voyeur or consumer of the scene but a living part of it.

And what is most important is what I do, what I undergo each day, rather than what I will show the folks back home when I return.

Act-Suffer-Learn: I act by forgetting to bring my video camera on my first day of riding. There is just so much to be attended to — finding the access point to the trail, packing my lunch and other necessities — and I am not accustomed to videoing my surroundings. So it’s not until I encounter a big, menacing timber rattlesnake coiled up on the train that I realize I can record this experience in memory but not digitally.

Not being able to video the rattler is one bit of suffering. Not having a cold beer with my lunch because I had forgotten to pack it is another. So is returning from the day’s ride exhausted because I’m not used to 40+-mile rides. Finally, I suffer because I can’t video the most beautiful wild animal I have ever come across — a porcupine. As I’m nearing the place where my car is parked, I see this roundish, biggish animal trotting along the trail ahead of me. It’s too small for a bear, too big for a groundhog. What is it? As I catch up with it I see the quills and realize it is a porcupine. But one whose quills are silver with bands of gold running across the middle of its back and its tail.

I learn that in spite of the trail running through the Pine Creek Gorge and in spite of the railroad that preceded the trail and the human habitation along the way this is wild animal country — their country, not mine.

So these shots — of the trail of the bottom of the Pine Creek Gorge — were made on the third day of my ride, when I returned to the northern section of the trail to cover its northernmost 6 or 7 miles.

And that’s another thing: I realize that there is this northernmost stretch of trail only when I see a map at the southern trailhead. I had broken camp the morning of my third day of riding, had everything in my car, and was intending to spend the night in a motel near the southern trailhead before driving home the next day. But once I saw that map I realized that if I were really going to ride the entire trail I would have to backtrack to the point at which I’d begun my first-day ride and go north from there. Act-Suffer-Learn.

But by the end of my first day of riding, I have suffered from the exertion of the ride and from the fact that, cameraless, I have missed recording my encounters with an awesome snake and a beautiful porcupine. Perhaps I have learned, though, not to forget the camera the next day.