Alan was the first surviving child of Leroy (Lee) and Dorothy (Dot) Wingard, born April 13, 1933. He was 13-1/2 years older than me. So that when I was a child, he graduated from high school (1951) and began college. I have very few memories of him from my childhood. He did live at home during college He attended what was then known as Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie-Mellon University) in Pittsburgh, and he had a number of part-time jobs to fund his way through college.

I do remember coming home from elementary school to find Alan rehearsing on the big upright piano that sat in the downstairs hall in our three-story house on Aylesboro Ave. He wouldn’t greet me as I entered; he’d just keep on pounding the keys. One summer, he had job managing the boat-rental concession at Raccoon Creek State Park, in Beaver County, PA, about 30 miles west of Pittsburgh. In my mind, I can see a photograph of young Alan (19 or 20?) in swimming trunks, squatting on a pier. He came home for a weekend with a wild raccoon he had befriended. I was thrilled when the creature would climb up my leg and stare at me.

Alan and I became closer when I went to high school (1960-1964). Actually, we became farther, because he no longer lived at home. But he promoted my literacy in those years. For my sixteenth birthday, he gave me a copy of Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio. I was too young to really appreciate it, but I cherished that book all the same. Another time, he gave me a copy of James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, another book that I was too young to appreciate in all its complexity, but Alan stressed to me the passage in which young Stephen Dedalus’ epiphany occurs. He is walking alone on the shore of Dublin Bay, meditating on his name, his education, and his future. He sees a vision of the mythical Daedalus and his son, Icarus, escaping on their homemade wings from the labyrinth of King Minos, Daedalus himself “a hawklike man flying sunward above the sea [who might be] a prophecy of the end he [Stephen] had been meant to serve and had been following through the mists of childhood and boyhood, a symbol of the artist forging anew in his workshop out of the sluggish matter of the earth new soaring impalpable imperishable being …” One of the most beautiful and, to me, inspiring passages in English prose. Dylan Thomas was another writer whom I learned from Alan to appeciate. We’d listen to a recording of Thomas’ radio play “Under Milk Wood,” and “A Child’s Christmas in Wales.” was another of his favorites. Alan loved the description of a young boy who “mittened manfully” on somebody’s front door.

Those words and others like them – the fabulous closing passage of Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, for instance – written by authors big and small fascinated Alan. He was a writer himself. He published a novel, The Graffiti Gambit, in 1970. He wrote and published poetry. He read voraciously throughout his adult life. In his last years, he was working on a novel (he hoped it would be the first in a series) about a resident of rural Maine who, with the help of his standard poodle, solves mysteries. I have a Ph.D. in English, but Alan was much more well-read than I, who read out of interest and necessity; Alan read out of love for well-shaped language. At one point, he was into the novels of Robertson Davies. He made arrangements to go to an organist convention in Toronto in hopes of catching a meeting with Davies. He did; he was thrilled. Alan would often quote Davies and other writers he admired. He’d say grace over a meal in Hebrew. He understood enough Greek to read certain parts of the New Testament in an unconventional way.

Alan loved to play with the English language. Just one example: he and I would be driving through the countryside of rural Maine, where he lived from 1988 until his death, and he’d point at a road sign that said “hidden drives.” Alan would call out, “lust, greed, envy ….” and laugh his big, full-throated laugh. He had a rich voice, as you might expect from a musician and choir director. Maybe that’s why he gigged as a radio host for a while when he was still living in Pittsburgh. I remember listening to him on the air as “Alan Winn,” on an a.m. station from Greensburg, PA. His show was, if not classical, certainly not rock ‘n roll, which Alan disliked. Anyway, he was reprimanded by management once for signing off with the phrase “Have a peachy keen weekend.” Radio WHJB (I think it was) was too stodgy for that. Alan was far from stodgy.

It wasn’t until the mid-1970s that I started spending much time with Alan. Oh, I visited him when I was in college and he was teaching at Lake Erie College for Women in Painesville, Ohio, not far from Cleveland. And I spent a night with him and his then-wife in Charlotte, N.C., when he was teaching at Belmont Abbey College. We stayed in touch by letter and telephone too, but not so much during my four years in the Navy. In 1976, Alan was living in western Massachusetts and no longer teaching in college. He drove to Pittsburgh for his high school class’s 50th reunion, and I happened to be visiting from Louisiana, where I was working on my Ph.D. He had a red MG-A convertible that was pretty cool. He also had a stash of weed that was very cool. I had discovered marijuana a few years earlier, as a sailor aboard the USS Forrestal. My first wife barred my use of it, though, after me and a group of shipmates were busted in June 1971 as we returned from the Mediterranean. By 1976, I was divorced and back to smoking weed, although I had no solid connection. That May, when Alan came for his reunion, we (and our father, Lee) went to brother Jan’s house for dinner one evening. In those days before there was an Interstate highway tunnel through Mt. Washington, across the Monongahela River from downtown Pittsburgh, to get to the South Hills suburbs you had to drive over the mountain on a two-lane road. Alan and I rode back to Squirrel Hill in his car. He pulled out a pipe, packed it with (as it turned out) his home-grown weed, and we boldly toked up as we zipped down McArdle Roadway with the convertible top down. For the next few years, summer or winter, my visits to Pittsburgh also involved a drive to New Braintree, Mass., to hang to hang out with Alan. And to return with a bag of weed. No charge.

Pot was one of Alan’s temporary enthusiasms. On one of my visits to him in Massachusetts, he told me he had given up smoking. As he told it, he was driving back from New Hampshire one day, looked at his bag of weed, decided it was “a drug” and threw it out the window. He had other fancies, or indulgences. One time he phoned me asking for a loan so he could fly to Portugal to meet a singer he’d become enamored of. Collectively, the authors he loved were another: he’d devour everything they’d written and read the books again, as with Robertson Davies. And he’d quote them often. Then there was wine, which for a while he drank copiously, too copiously. He’d have a jug on the table and dinner and just keep on hitting from it, not even pretending to offer more to others. He loved women, generally and particularly. It sometimes seemed like he’d fall for his next wife while still married to her predecessor. Curiously, when he met Linda Ringeisen, whom I recall was first a co-tenant in an apartment in Boston, and they eventually married and bought a house, she settled him down. He was married to Linda going on 40 years when he died.

As a younger man Alan was handsome. He was clean-shaven, as men were in the 1950s, until he grew out his beard and kept it till the day he died. He was unconventional in his dress. I don’t recall ever seeing him in shorts, and even in summer he always wore a long-sleeve shirt; he never wore t-shirts even though they came into fashion while he was still young enough to wear them. He favored khakis over jeans, and would dress up an old sports coat with a v-neck sweater. As he got into his 80s, he developed kyphosis, to the point where he looked like a walking letter C. Eventually he had to use a stick to help him walk. Of course, this debilitation stopped him from doing yard work on the acreage. On subsequent visits, alone or with Karla, we’d ride into Rockland or Camden, Maine, to do shopping or just to check out the scenery. Alan would greet everyone he saw with a smile and a few friendly words. Once, when he was in his mid-80s, he complimented a woman, who was by no means young and no longer attractive, in a grocery store. She looked surprised, and Alan apologized and said, “Oh, I hope you didn’t think I was hitting on you!” I cringed inside, but that was Alan. Even when his looks were gone and his body was bent, he never lost his eye for women.

He also retained the strength in his arms and shoulders. When he would embrace me, frail as he otherwise seemed to be, his upper-body strength was surprising. On one our last visits, he took Karla and I hiking up a steep hill to see the long view out over Penobscot Bay. He used a stick, but he made the climb. His fitness routine, such as it was, consisted mostly of walking. Where he lived in Maine, at least once a day as long as he was able he’d walk down the long lane from the house and along the dirt road to the Miller Cemetery. When I’d do that with him, he’d marvel at the surroundings, at the birdsongs, at the widlflowers, and the trees. Alan never lost his sense of wonder for the natural world.

I’ve never known anyone who laughed like Alan did. He loved to laugh. He loved jokes, and as I said, wordplay. He’d laugh hard, from deep in his chest. And often his eyes would overflow with tears. His laughter, like other aspects of Alan’s life, was uncontrollable. That is not to say he would laugh in inappropriate places or at inappropriate times, but once he got started he would just laugh and laugh and laugh. He’d laugh at jokes, at puns, in the telling of his own stories. In that last case, his eyes would widen and bulge and he’d lean toward you at the punch line. My words cannot do justice to Alan’s sense of humor, but I will share two of his favorite stories. (Or my favorite Alan stories.) When I’d visit him in Massachusetts and we’d get high, he’d open his book of cartoons by B. Kliban, and we’d just get helpless with laughter. One anecdote that made an impression on impressionable young me came when Alan returned from his stay in Scotland. Seems he was drinking in a second-floor pub in Edinburgh when someone rushed in from the store below and asked, breathlessly, “Is there a doctor here?” Silence; then someone asked why and the guy said, “Well, I’m not sure, but I think we have a case of smallpox downstairs!” Silence again; then someone called out, “Bring it up! We’ll drink anything!” And Alan would roar with laughter. (For the rest of his life, he’d often say “aye” instead of “yes.”) Then, when Alan was studying music at Carnegie Tech (now Carnegie Mellon University), he was in a coffee shop off campus and a woman came in and sat near him. Alan asked politely, “Do you mind if I smoke?” To his then and future delight, the woman answered, “I don’t care if you go up in smoke!”

Of Lee and Dot Wingard’s four surviving sons (the first having died in infancy), only Alan was adept at working on cars. He wouldn’t think of paying a mechanic to change his oil. And his cars were always small imports, like Volkswagen Beetles, which he would pronounce in the German way: “Folksvagen.” One time, I helped him replace the brakes on his MG-A. Later, he favored Mazdas, which he would often buy in Canada, where there were models you couldn’t find in the States. He phoned me one time and said he was suffering from “Miata fever.” At the moment, I didn’t realize that a Miata was Mazda’s sports car, and I thought this was a physical health problem. Alan had found one for sale in Wilmington, Delaware. He flew down there, picked up the car, and drove it back to Maine, stopping at our house in Bethlehem, PA, on the way. It was sharp: a red convertible with a 4-cylinder engine that could really scoot. He got a vanity tag for it that read “Bach” after his musical hero. Imagine Alan, bearded and grinning, driving the back roads of Maine in that Miata with his black standard poodle, MaryMargaret, in the seat beside him. Long before the concept of emotional-support animals came about, Alan was always comforted by his poodles.

Alan loved all animals, particularly small ones. In his 40s, when he lived in rural Massachusetts, he had cats at his house. He talked to them and sang to them. There were chipmunks in the area, and a neighbor called them “chick munks.” Alan morphed that into calling them “garbanzo munks.” When Alan married Linda Ringeisen and the couple moved to Maine, dogs entered his life. Linda had a dog, a mixed breed called Dougal, and eventually started her own business as a dog groomer. They met a couple who bred standard poodles, and for the last 30-some years of his life, at least one standard poodle shared their home with them. Linda also had a horse, Arwin, and one motivation for them buying property and some acreage in rural Maine was so Arwin would have a barn. When Arwin died, they buried him outside the barn, which became Linda’s grooming studio.

Alan never did so well with his children –a daughter and two sons, born of two different wives – but, God, he loved his dogs! Whenever Karla and I would visit “Camp Paradise,” as Karla dubbed their place, humble though it was, and we’d go out on errands, Alan wanted us to bring whatever dogs he had at the time along. That wasn’t always practical, but sometimes we did it.

Alan died slowly after hospitalization for, first, Covid, then a urinary tract infection. He came home from the hospital just before Christmas, 2022, and was under hospice care. I hoped he’d get his strength back from being in familiar surroundings, but no. My younger brother Mark came to Maine from his home in New Mexico to be with Alan in hospice. As far away as Mark lived, he was the only available one of the Wingard boys, but he was also the best suited, having studied hospice care in his younger years. Mark and Alan’s wife, Linda Ringeisen, were at his bedside when he passed. So was a stray cat, called “Peter Nigel.” This cat had showed up at the house after Alan came home from the hospital, stayed, and was taken in. The day Alan died, Peter Nigel, for the first time, jumped up onto Alan’s bed and lay with him. He must have been Alan’s escort to the other side.

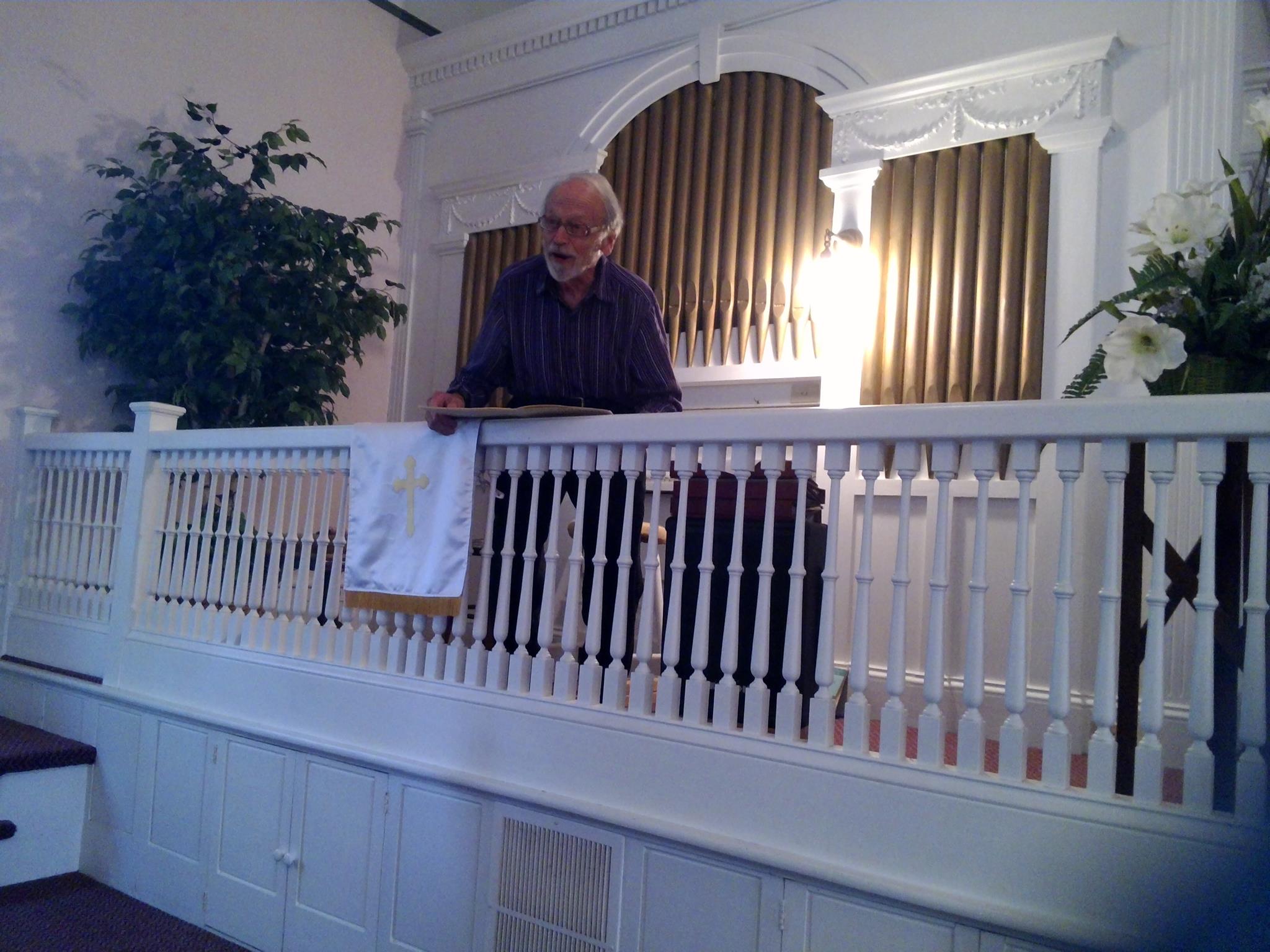

Alan’s greatest enthusiasm was the pipe organ. He would say that when Dot took him to Edgewood Presbyterian Church when he was young — he had to be pre-teen because the family moved into Pittsburgh when he was thirteen — he was blown away by the sound of the organ and knew that he had to learn to play it. When I was a kid, I knew only that Alan played piano and was into, as Lee called it, “that long-hair stuff,” aka classical music. I don’t know when he started on the pipe organ, but I do remember seeing the insides of organ pipes in the basement of our home in Squirrel Hill. I think he was trying to build an organ himself. At some point, he came under the tutelage of a man named Donald Kettering, who was music director at the massive neo-Gothic East Liberty Presbyterian Church, just a couple of miles from our home. Maybe it was Kettering who taught Alan to play the pipe organ. Alan was proud of Kettering inviting him to direct the church choir at one point. When he made a visit to Pittsburgh on the occasion of brother Jan’s 50th wedding anniversary, he arranged to play the organ at ELPC. His main source of income in later years was teaching elementary school music, but he supplemented that and indulged his first love as an organist and choir director at churches in Downeast Maine. His longest gig was at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in Waterville. Alan knew the history and the the quirks and limitations of each organ he played. At St. Mark’s he supervised the renovation of the organ. (The picture at the top of this post is from a concert he perfomed on an early-19th-century organ at a small church in Sonon, Maine, in the summer of 2015.) At some point he had a pipe organ built for him and installed in the house at Camp Paradise. The instrument was unusual in that it could be collapsed — the keyboards, the foot pedals, the pipe chest — and moved. His plan was to haul the organ around to schools in hopes of igniting in young children the passion he had felt on hearing a pipe organ for the first time back in Edgewood, PA. I don’t think he ever actually did make these road shows, but every time we’d visit there was time to hear Alan play it. His composition that ends this post was played on that organ at Camp Paradise.

There’s a song by Crosby, Stills, and Nash called “Southern Cross.” In it are the lines, “I have my ship and all her flags are a-flyin. She is all that I have left, and music is her name.” Music was indeed the ship that Alan sailed. Many times he told me how, as a teenager, her heard the pipe organ at Edgewood Presbyterian Church for the first time and was mesmerized by the sound. He vowed to one day play the pipe organ himself. In high school, he joined the choir at the magnificent East Liberty Presbyterian Church in Pittsburgh (built by the wealthy Richard King Mellon) and came under the tutelage of the choir director and chief organist, Donald Kettering, and learned to play the organ. For the rest of his life, Alan was a church organist and choir director himself, although he was also an elementary school music teacher. At one point while living in Maine, he had a pipe organ built and installed in his house. He and his wife, Linda Ringeisen, connected the barn to the house, and in that space was Alan’s music studio. The organ he had built was unusual in that it was collapsible; the keyboards and foot pedals and the pipe chest could be folded together. Alan’s idea was to be a kind of Johnny Appleseed of the pipe organ, hauling the instrument to schools to play it for children in hopes of igniting the same fire in them that he had experienced as a young man himself. From his home studio, Alan also composed music for the organ and arranged scores for voices. Of course, he had a strong baritone voice himself. Embedded here is one of his last compositions, “Pavane for the Healing of the Earth.” Give a listen; it is Alan at the keyboard.

Sail on, Alan! I will love you as long as I live! I’ll think of you when I hear the radio playing Bach, or even good piano. I’ll want to call you when something funny happens. I know you’ll laugh.

wow!! 65Cycling the Pine Creek Trail: The Rhetoric of Travel

LikeLike

Hi Joel,

I was a piano student of Alan’s. We used to have lunch together and he would laugh and laugh like no one I have ever met. He was a joy to be around. I visited him and Linda and pups at the farm in Appleton and we drank sweet red wine that I still love to this day. I took the photo of him and Willoughby behind my office in Waterville. I keep it to this day and all the tapes of my piano lessons with him. He was such a joy. I’m blessed to have known him. Thank you for sharing your stories about him. They certainly made me smile.

LikeLike

Alan was indeed a complex human being. A deep thinker, a seeker of esoteric knowledge. A romaticizer of his interaction with life around him. A brilliant musician!

As a child I tried desperately to understand and connect in my 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 year old self with a man who spoke a different language.

His portrayal of father-ness was indeed a role with the focal point on self, not other.

When visiting him following a cardiac event, I arrived at his hospital room one day to observe his reunion and interaction with his standard poodles. In that moment I realized that he loved those dogs wholeheartedly in a way he could never love his children. Children are messy and can really throw a wrench in one’s life. Dogs are safe.

Uncle Jan, you also opted out on me and my brother when my dad and mom divorced. You never reached out. I have no specific memories of you and only recall a photo of you holding me.

Oh, and maybe you could correct the brief sentence regarding his children from two “different women” and replace the term with “wives” . My brother and I are not bastards.

LikeLike